I am very interested in what way we are genetically and biologically unique, and we should compare ourselves with them,” said Svante Pääbo.

If you like, they define present-day humans as a group.

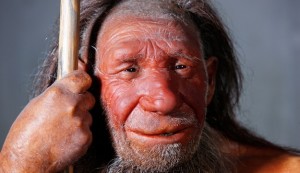

"They are indeed our closest evolutionary relatives.

“Our research team is obsessed with Neanderthals since twenty years,” he said, explaining why. It’s quite recent, Svante Pääbo noted about 1,400 generations ago, they were still here. Shortly after modern man appeared on the scene, the Neanderthals also disappeared. In eastern Eurasia, they encountered other forms of hominins that are now extinct and about which we know less. They encountered the Neanderthals in western Eurasia. They began to wander out into the rest of the world less than a hundred thousand years ago, and they were not alone. But modern humans – meaning those whose skeletons were similar to ours and who are the ancestors of today’s humans – appeared in Africa much later. The first human beings appeared in Africa and spread to Asia and Europe around two million years ago. Svante Pääbo was grateful for the cordial introduction and the Nobel Prize. “This information has given us a completely new reference point for understanding our evolution,” she summarised. These include the mapping of Neanderthal DNA and the discovery of a new human species – the Denisovans. She highlighted how Svante Pääbo’s diversity of interests and studies, for example in Russian and Egyptology, created the conditions for his later discoveries. Pääbo´s account of his work in an area of research that I think is of unusually broad interest, namely human evolution,” began Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam, professor of vaccine immunology and a member of the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, once everyone was seated in the warmth of the auditorium. “It is with great excitement that we look forward to listening to Dr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)